Palm Sunday

Liturgy of the Palms

Year C

Gospel Reading: Luke 19:29-40

I love the film, Memento. What I love most about Memento are the little nuggets of plot-development hidden in plain sight, and how those becomes crucial for appreciating the entire story.

At the beginning we learn about the main character, Leonard Shelby, who suffers from extreme short term memory loss because of a severe brain injury incurred at his home, seconds before witnessing the murder of his wife. Just as Leonard witnesses his wife suffocating to death, an armed robber violently strikes Leonard on the head, and from that point forward in life, Leonard's long-term memories are haunted by that final, enduring image of his wife's suffocation. He then sets out on a life-long quest to find those who killed his wife, and to satisfy justice.

Fast-forwarding to the end of the story, a detective named Teddy is murdered by Leonard Shelby. Leonard thinks Teddy was part of the conspiracy to murder his wife, but of course, because Leonard suffers from severe short-term memory loss many people throughout his life after that event—including Teddy—become suspects of that conspiracy accidentally, even though they aren't necessarily guilty. All Leonard wants in life is to find those who conspired in the murder of his wife, and he will do whatever it takes to bring vengeance upon them. But we come to find out in the end of the story that so much more had been going on all along, and best of all it was hidden in plain sight, right in front of our very eyes.

Spoiler Alert: Just before the death of Teddy, the detective, we learn some mind-blowing details about Leonard's life. First we learn that Leonard Shelby's wife didn't actually die the night her husband had his brain injury. She survived that night, but Leonard doesn't remember that because he suffers from extreme short-term memory loss after his brain injury. All he remembers is her suffocating. Every day, he still thinks she's dead. And eventually, over time, she does die; and she's even truly dead by the time the events within the film take place. However, as the plot progresses, we learn that Teddy, the detective, already brought Leonard to the real attacker, and Leonard already avenged his wife, but Leonard doesn't remember that either. Finally, as if those tidbits of information weren't shocking enough, we also learn the most shocking fact of all: Leonard actually murdered his own wife, by assisting her in committing suicide. It turns out that after his injury, his wife became so depressed with having to live with his short-term memory loss, that one day she tested him. She was diabetic, and in need of regular insulin shots, so she tested him over and over again by requesting him to give her shots, minutes apart from each other. She eventually died of overdose. That was her way of coping with what she perceived to be the loss of the real man she loved and married. But he doesn't remember ever assisting her suicide. Leonard even gets a tattoo on his hand to assist his memory about that, but the tattoo doesn't help. All throughout the film we are shown that tattoo, and the message is in plain sight, but Leonard interprets it differently. Even when you hear or see that phrase tattooed on his hand repeated over and over again ("Remember Sammy Jenkins"), if the viewer does not stop and think about it's significance, or its significance is misunderstood, it is possible to watch the entire film and walk away from it with a very different message than what the director intended.

This is true with the theological nuggets we find scattered throughout Luke's gospel. If we overlook or misunderstand some of them hidden in plain sight, we might walk away from the gospel story with a very different message than what Luke intended. And in today's reading, we have one of those theological nuggets. It is found in Luke 19:39b–40, which the ESV translates this way:

"Teacher,

rebuke your disciples." He answered, "I tell you, if these were silent, the very stones would cry out."

Usually, when I'm preparing a meditation for any given day, I try to harmonize as many of the lectionary readings as possible and unite them into a common theme. But with this week's lectionary readings, something very different happened as I was studying. I became stuck on this one very brief statement.

Do you want to know why I've been stuck on that passage all week long? It's because the Greek text underlying that English Standard Version does not say that. And I've been hung up all week on what it actually says, and why Jesus said that. What the Greek text actually says is this:

"Teacher, rebuke your disciples!" And answering, He [Jesus]

said: "I say to you-all, that when these [disciples] become silent, the

stones will cry out!"1

As I perused through my biblical commentaries, I noticed that this passage is usually explained in one of two ways. It's either explained as a comparison between animate human beings (i.e.

disciples) and inanimate objects (i.e. stones), illustrating somehow, some way,

that Jesus deserves to be praised by His creation, e.g. "If people stop

praising Jesus, surely these stones on the ground will instead!", or it's expressing a contrast of faith between the Pharisees and stones, illustrating that even stones understand

their Creator better than Pharisees.2

With either option, I'm left unconvinced. And I think it's important to convince others to remain unconvinced as well. But in order to reach any conviction about the meaning of this theological nugget (whether one agrees with me or not), it always helps to start by asking obvious

questions. For instance, why does Jesus mention stones? Is it merely because they

can be classified as inanimate objects? In that case, wouldn't the

reference to stones be somewhat arbitrary, as though Jesus could have

mentioned any other static material on this planet—such as

trees, saddlebags, or belly-button lint—to illustrate the same point? He just mentioned

"stones" for no essential reason, I guess. Perhaps it was the first thing that

popped into His mind, someone might say. That sounds like a dubious proposal at best.

What if the whole point of mentioning stones is simply to point out how lifeless the faith of the Pharisees is? Although I don't doubt that the faith of many Pharisees was dead, I don't think that clarifies what Jesus actually said. Again, all one has to do to notice my contention is to simply look back at the

text. Re-read it a few times. Such explanations about dead pharisaical faith hardly accounts for what Jesus actually said in context. (Besides, if you've read the previous 18 chapters of Luke's gospel, you should have already realized that their faith was dead.) So let's go back to asking obvious questions again.

Why must stones cry out if Jesus' disciples are silenced? That is what the text actually says.3 Is it because stones perceive God better than Pharisees? That doesn't answer the question. That

begs the question. If the point, supposedly, is that Jesus is also worthy of praise

by stones, then why aren't the stones also crying out at the same time as the

disciples? Why wait until the voices of Jesus disciples are silenced?

I think that in order to make sense of Luke 19:39b-40, we need to review the story of Luke's gospel briefly to find other tidbits hidden in plain sight for us.

In the close context of 19:39b-40, Jesus is on his way into Jerusalem for the

first time in Luke's gospel. Toward the beginning of the Lukan travel narrative, Jesus set his face toward Jerusalem (9:51), and he wouldn't cease ministering

to people until he was silenced in Jerusalem. Throughout Luke's travel narrative, that message of reaching

Jerusalem and being killed by Israel's rulers is repeated three times for

emphasis (9:22, 44; 18:31-33). Alongside that tidbit, Luke's travel narrative is also filled with allusions to soon-coming

judgment upon Jerusalem for rejecting their King. Even before Jesus arrives in Jerusalem, the shepherds of Israel have no excuse for rejecting him as their King, and they also have no excuse for refusing to repent of that rejection.

In the middle of Luke's travel narrative, we find one of those nuggets hidden in plain sight. But there, Jesus does more than make allusions to Jerusalem's judgment; he emphatically declares that its temple is forsaken, abandoned by God, because they were not willing to accept His terms

of peace:

O Jerusalem, Jerusalem, the city that kills the prophets

and stones those who are sent to it! How often would I have gathered your

children together as a hen gathers her brood under her wings, and you were not

willing! Behold, your house is forsaken. And I tell you, you will not see me

until you say, 'Blessed is he who comes in the name of the Lord!'" (Luke

13:34-35)

Now fast forward to the end of Luke's travel narrative,

where Jesus is about to leave Jericho and enter into Jerusalem for the first time. There we find Jesus telling one last parable to his disciples en route to his triumphal entry (19:11-27). In that parable Luke goes out of his way to emphasize the allegorical relationship between

Jesus' servants in Jerusalem and Himself entering that city as their King. By the end of the parable the "wicked servants" and "enemies" have proven themselves hostile and indignant toward their King. Not only had they perpetuated gross injustice while the King was away (similar to the claim above about "killing the prophets and stoning those who are sent to it"), they also would not repent or accept His terms of peace and reconciliation. They refused to let Jesus rule mercifully over their merciless kingdom. For that reason, the King decrees that they be slain upon his arrival. With the merciful, he would show himself merciful. With the blameless, he would show himself blameless. And with the crooked, he would make himself seem torturous (Psa. 18:25-26; 2 Sam. 22:26-28). Jesus saves those who are humble, but his eyes are on the haughty to bring them down.

After that final parable, Jesus follows his prophetic cry with more sovereign

lamentations explicitly directed at first century Jews in Jerusalem (Luke 19:41–44):

And when he [Jesus] drew near and saw the city

[Jerusalem], he wept over it, saying, "Would that you, even you

[Jerusalem], had known on this day the things that make for peace! But now they

are hidden from your eyes. For the days will come upon you, when your enemies

will set up a barricade around you and surround you and hem you in on every

side and tear you down to the ground, you and your children within you. And

they will not leave one stone upon another in you, because you did not know the

time of your visitation."

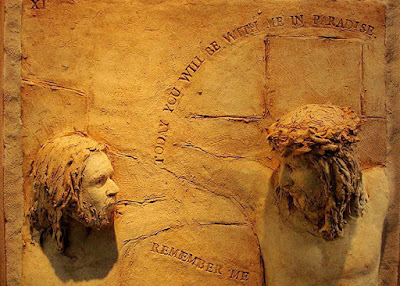

Much like the prophet Habakkuk's reasons for thundering woes against Jerusalem, it is this incessant rejection of Israel's King by their rulers which leads to the toppled stones of the Temple's ruin crying out against those perpetrating violence and injustice within:

You have devised shame for your house by cutting off many peoples! You have forsaken your life! The stone shall cry out from the wall, and the beam from the woodwork respond: "Woe to him who builds a town with blood and founds a city on iniquity!" (Habakkuk 2:10-12)

I believe these nuggets of prophetic woes scattered throughout Luke's gospel are designed to clarify what Jesus said to Pharisees during his triumphal entry. The "Wisdom of God" repeatedly told Jerusalem that His prophets and apostles would be sent to them, but they would not listen. Instead, the harlot-city would silence the Lord and His servants

(Luke 11:49–52). With that trajectory toward rejection and judgement, when we reach the point of Jesus' triumphal entry into Jerusalem, and we see the Pharisees still attempting to silence Jesus' disciples (19:39b), Jesus' response makes perfect sense if its understood as a prophetic, Habakkuk-like cry toward Jerusalem and its corrupt rulers. As Jesus' disciples cry out, "blessed is the King who comes in the name of the Lord! Peace in heaven and glory in the highest!", the Pharisees tell Jesus to rebuke the disciples. So when Jesus responds to the Pharisees, its trajectory is directed toward the harlot-city, toward Jerusalem's rejection and consequent judgment:

"I say to you-all, that when these [disciples] become silent, the stones will cry out!"

Little did the Pharisees know that the prophets, apostles, and disciples of Jesus were living stones of God's new

temple-building project (Eph. 2:19-22; 1 Pet. 2:4-6), so when those stones cry out for vindication, judgement is right around the corner because their voices are heard by Jesus himself in his heavenly temple. This was the

Lord's mysterious and marvelous plan all along. It is through the incarnation, death,

resurrection, and ascension of God's incarnate Son that the blood of all

the prophets and apostles, shed from the foundation of the world, would cry out and finally receive vindication for all their suffering. They witnessed to the truth of God and His reign over all, and their shed blood would be charged against Jesus' generation (11:49-52). That generation would be definitively judged.

All of this brings us back around to the passage in Luke in which Jesus prophesies about disciples being silenced for their testimony of Jesus' lordship, and stones crying out as a result. I think its clear that Jesus' woe alludes to the Habakkuk woe spoken to the leadership of Jerusalem. In that prophecy, the stones of the temple walls cry out because of tremendous injustice perpetrated within its walls and upon God's people. Historically, it was during the Jewish wars (66—70 AD) that Jerusalem

and its idolatrous temple were finally destroyed by the Lord's visitation. Because Jerusalem did not know the time of her visitation, and the testimonies of those who bore witness to Jesus were silenced, the stones would cry out from the wall: "Woe to him who builds a town with blood and founds a city on iniquity!" But "blessed is the King who comes in the name of the Lord! Peace in heaven and glory in the highest!"

At this time, someone might be asking, What is the bottom line of all

this?

That's a good question. How does this affect our understanding of the gospel story, so that we don't miss out on what the director envisioned for us?

A few responses immediately come to mind:

First, because there is a pervasive tendency among Christians to

"proof-text" scripture into emotional and spiritual nonsense, it's

always important to remember that the gospels are about real life, flesh and blood, pus and guts, historically documented events. Even the prophecies of Jesus were not some kind of gnostic, esoteric, mystical future cataclysm. Certainly they were about future events. However, Jesus was addressing historical

events which would come upon his own generation (Luke 7:31; 11:29,30,31,32,50,51; 16:8; 17:25; 21:32). This is often missed, and the

gospels misinterpreted, because the fulfillment of those divinely imposed judgments within his generation are not taken into

account by the average, run-of-the-mill Christian. It is absolutely vital to the understand and acknowledge that the destruction of Herod's idolatrous temple is the most significant historical event in Israel's history. And that was clearly on display in Jesus' mind throughout Luke's gospel. That event is the definitive end of the old covenant, and the decisive action which vindicates all the disciples of Jesus Christ in the first century. The entire course of history dramatically changed after that cataclysmic event.4 And it's not a mere coincidence that Jesus' death, resurrection, and ascension strike the match and light the wick leading to that cosmic judgment. So it's important to familiarize yourself with those events, and to

read scripture through the lens of those concrete historical promises.

Second, remember that because every statement within the gospels is part

of a much larger story, we need to search, discover, and meditate upon the nugget-like tidbits scattered throughout the story. Those tidbits are not tertiary details. Just like in Memento, if they are overlooked or underestimated, the director's vision behind the story can be misunderstood. If Jesus' explicit promises regarding Jerusalem's destruction in that generation are overlooked or underestimated, then the first century Jewish-Christian context of New Testament theology can be misunderstood.

Finally, but just as important as the previous points, this brief tidbit of Luke's gospel teaches us something significant about the character of God. Throughout evangelical circles, Jesus is often mistakenly portrayed as the "light" version of the old testament God. Just like Budweiser has their light beer, Jesus is the old testament Father's light-bodied persona. He's low on calories, while still offering the full-bodied flavor of the original Divine recipe, which we all love. As such, the Church mistakenly thinks of Jesus' character differently than the Father's, and that is a mistake. Both Jesus and YHWH are love (Deut. 7:9; Psa 36:7-10; Joel 2:13; I John 4:8,16). Both Jesus and YHWH are a consuming fire (Deut. 4:24; Heb. 12:29). Jesus' gospel was about consuming fire and love. It is our God, Jesus, who considers it just to repay with affliction those who afflict his children, and to grant his children relief through affliction by inflicting vengeance upon those who do not know Him and on those who do not obey the good news of our Lord Jesus (2 Thess. 1:6-8).

In fact, it is precisely because

Jesus is love, that we must heed Jesus' warnings and not reshape the love of God into our own American

idol. When we see Jesus loving all those around him, we also need to

see that love as an expression of warning his own generation of consuming fire—of tangible, down-to-earth judgment upon flesh and blood because of their exceedingly great wickedness. It's also important to see Jesus as the son of man coming to judge them (Matt. 10:23; 12:40-42; 13:37-43; 16:27-28; 24:30-34). As the son of man, part of the way he loves the world is by waging war upon its evil every day; and that is a good thing. It is good that Jesus must continue waging that war until

he has put all his enemies underneath his feet (1 Cor. 15:25). Only then will true peace cover the earth as the waters cover the sea. Jesus was indeed the

most loving human in history, and yet his love did not violate the free will of

those whom he loved, and so he warned them about how destructive their idolatry

had become, and he waged war against those who refused to accept his rule. In an thoroughly corrupt and evil generation, there can be no peace without war. Thankfully, though, most people throughout the world are not destroyed. Instead, many are confronted by the heinousness of their own sins and destructive tendencies, and are brought to their knees before King Jesus. God graciously makes Himself available to them, and when they sincerely repent and surrender to him, they are shown mercy, and they receive new life in Him.

Another way to look at Jesus' prophetic warnings is like this: Jesus

loved the world so much that he gave his life for it, but there comes a point

in time when an entire generation needs to acknowledge that Jesus is Lord of lords and King of kings and he knows our needs better than we do. He knows how to establish and cultivate peace on earth better than we do. If parts of his creation become rotten to the core, he knows best, and he knows how to uproot and plant something new and healthy in its place if need be. In a world where the ground is

cursed and humanity is exiled from the presence of God, the whole process of uprooting, tilling the soil, and planting new is an expression of love. The fact that the Gardener even draws near to his fields all over the world and tends to their needs worldwide is a good and beautiful thing.

Within the exhortation of our Lord about disciples being silenced and stones crying out, is his decree to tear down the diseased house of the old covenant in order

to build an exceedingly glorious temple in us. And his temple-building project isn't over yet. His global gardening project is not over yet. There still is a lot of work yet to be done. Don't be bashful about that, and don't be afraid to walk in the way of Christ's suffering for that. Rather, walk humbly in the way of his suffering that you may also share in his resurrection. Believe

that, witness to that, and proclaim that. That is true, just as God's love for

the world is true, and his warfare against evil every day is true.

If you start thinking about how gloomy and corrupt our current generation is in comparison with the glorious future promised for God's kingdom, don't be worried about it. Continue witnessing to the good news of King Jesus and his terms of peace for the world. He is always far more willing to give mercy and extend favor than we are to receive it. He is called the King of Peace for good reasons.

And if you ever become anxious about these temporary, mortal bodies of ours returning to the soil, leaving the fruitful praise of our lips silenced, don't worry about that either. Other stones of God's temple will

continue that proclamation. Blessed indeed is our King, Jesus. He is the reason why there is any peace on earth and in heaven. Glory to Him in the highest!

Almighty and everliving God, in your tender love for the human race you sent your Son our Savior Jesus Christ to take upon him our nature, and to suffer death upon the cross, giving us the example of his great humility: Mercifully grant that we may walk in the way of his suffering, and also share in his resurrection; through Jesus Christ our Lord, who lives and reigns with you and the Holy Spirit, one God, for ever and ever. Amen.

1. This is my translation of the Greek text: Διδάσκαλε, ἐπιτίμησον τοῖς μαθηταῖς σου. καὶ ἀποκριθεὶς εἶπεν· Λέγω ὑμῖν, ὅτι ἐὰν οὗτοι σιωπήσουσιν, οἱ λίθοι κράξουσιν

2. Darrell Bock, a reputable Lukan scholar, offers a variant of this, claiming that inanimate objects—like stones—"have a better perception of God than the people He came to save." Even though that is a clever and truthful way of spinning what Jesus actually said, I still think that greatly misses Jesus' point. See Darrell L. Bock, Baker Exegetical Commentary on the New Testament (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Books; 1996), p. 1,547

3. A few other technical details are worth noting. As I have argued here and elsewhere on my blog, I think mainstream english translations of the New Testament are based on an interpretation disconnected with the destruction of Jerusalem as foreshadowed in the consistent typological messaging of Israel's prophets. To me that disconnect seems clear for grammatical reasons as well. For example, in the ESV we find the insertion of "very" into the text (which isn't even implied in the Greek). In English, the insertion of "very" could be construed as connoting an idea of contrast between animate and inanimate objects, which is unnecessary if Jesus is actually prophesying future historical events related to Jerusalem and its temple. Another disconnect is seen in the confusing translation of "were silent" and "would cry out" like it's a conditional subjunctive, which it's not in Greek. Both verbs are future-active-indicative. The ἐάν with a subjunctive verb would express a probable or hypothetical future condition (which is why the conditional conjunction is translated "if" in the ESV), but the indicative verbs remove that probability and instead express certainty (which is why ἐὰν here is better translated as "when").

4. See Mark A. Noll, Turning Points: Decisive Moments in the History of Christianity (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic; 2008, eighth ed.), pp. 23-46